Artwork: "Minerva" by April Jakubec

“Minerva” is named after the Roman goddess of wisdom and the arts.

This portrait captures a Latina woman enjoying the outdoors as the wind blows through her flowing hair. Flowers are clustered together to form a face mask, hiding her smile, but showcasing strength in her exposed eyes. The blooms represent what good can stem from these strange and difficult times (innovation, connection, kindness, etc.).

Women of all ages and backgrounds have strongly identified with my bright and positive portrait style, and have been able to see themselves in the pieces. I intend for this piece to show that compliance with health and safety regulations is strong, fashionable, and even fabulous.

April Jakubec's art is published through the Punto Urban Art Museum, a program of North Shore CDC. Learn more about the museum's programs and their "Free COVID Resources."

Starting in March, we began hearing story after story about ways CDCs were responding to the COVID-19 health crisis and the economic repercussions that reverberated throughout their communities. More recently, we surveyed our members to better understand the ways in which Massachusetts CDCs are responding in aggregate to this unprecedented crisis. What follows is a description of a few of the stories that we heard, as well as what we learned as a result of our Member Survey.

Back in March, we learned that many CDCs noted food security as a top concern in their communities and responded through food distribution efforts:

- Allston Brighton CDC mailed out Stop & Shop cards, so that their tenants could buy food.

- The Coalition for a Better Acre's Youth Development staff, who usually run its after-school program, became its food distribution team.

- Groundwork Lawrence launched "virtual" markets, to replace its in-person farmers market.

- Franklin County CDC responded to the crisis with a new outlet for frozen produce.

We also heard about the many ways in which CDCs are shifting their key services online, such as Island Housing Trust which held its first remote homeownership lottery via video conference. Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción (IBA) adapted its culture-driven youth workshops to an online format and turned their annual Festival Betances into an online event.

Early on we also learned that many CDCs were establishing emergency relief funds to help families with rent, food and other necessities. For example, Housing Assistance Corporation established the Cape Cod COVID-19 Workforce Housing Relief Fund to assist with past due rent, mortgage payments, and other housing-related expenses for current, year-round Cape Cod and Island residents who are losing income. We have also been working with CDCs across the state, like Dorchester Bay Neighborhood Business Loans (DBNBL), which is serving as a resource hub for small businesses in need of COVID-19 resources and guidance.

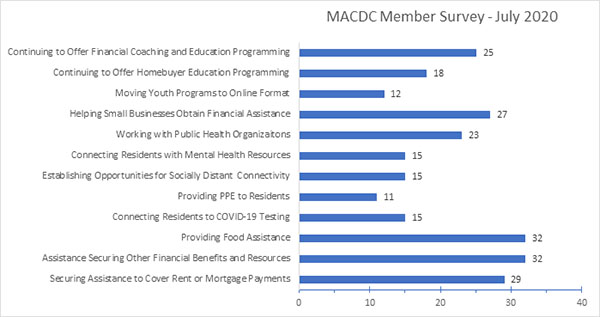

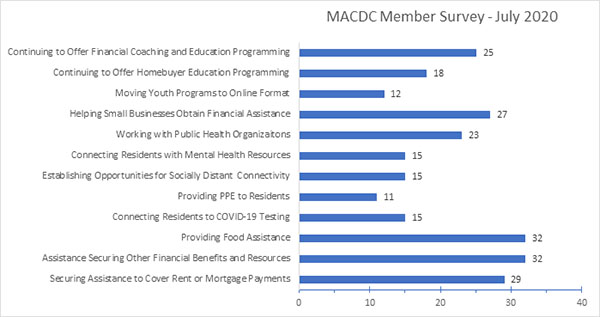

As we moved into month five of the crisis, MACDC sought to understand the cumulative nature of the work in which MACDC members are engaged. At the beginning of July, we sent a survey to our members. You can see some of the results of the member survey on the graph below.

Number of Members providing Specified Responses to COVID-19 in Their Communities, Out of 47 Total Respondents

Number of Members providing Specified Responses to COVID-19 in Their Communities, Out of 47 Total Respondents

Our anecdotal observation that many of our members engaged in food distribution efforts was supported by the survey responses indicating that more than two-thirds of MACDC members reported providing food assistance in their communities. We also learned that more than half of CDCs worked with community members to secure assistance to cover rent, or mortgage payments and over half helped small businesses to obtain financial assistance and other support.

In addition to these responses to economic challenges in their communities, we learned that many MACDC members stepped up to help mitigate disease spread. Half of respondents indicated that they partnered with public health organizations, close to a third of respondents indicated that they connected residents to COVID-19 testing, and close to a quarter of respondents said that they provided PPE to community residents.

Massachusetts CDCs’ have succeeded in slowing the spread of COVID-19 in their communities, as illustrated in a recent New York Times article highlighting the work of the Neighborhood Developers in Chelsea. Despite Chelsea being designated as a COVID hotspot, The Neighborhood Developers only had eight reported cases which is about a tenth of the rate of surrounding community.

Beyond the efforts to mitigate physical health concerns, many CDCs engaged in efforts to reduce potential negative mental health impacts of social isolation. Eighteen out of the forty-seven survey respondents reported that they connected residents to mental health resources. Additionally, close to a third of respondents said that they had established opportunities for socially distant connectivity. These opportunities included virtual exercise and art classes, participation in the Front Steps Project, and hosting outdoor events.

We know that while every CDC in Massachusetts is stepping up to support their communities, each CDC is doing this in a unique way suited to their community’s strengths and needs. For example, just last week, we learned that North Shore CDC and the Punto Urban Art Museum recently released twenty-five free artistic educational resources to raise awareness of COVID-19 safety measures in low-income, primarily Spanish-speaking communities.

In years past, individual CDCs have had to respond to local disasters like the tornados in Western Mass in 2011 and the Columbia Gas explosions in Lawrence last year. Each time, the local CDCs rose to the occasion to help residents with emergency shelter, food and relief while also helping those communities rebuild. Now, in the face of a global pandemic that is impacting the entire Commonwealth, CDCs across the state are showing that community development is a core component of our disaster resilience, response and recovery system. Unfortunately, it looks like this could become a permanent feature of community development across the United States. Fortunately, CDCs are demonstrating that they are up to the challenge.

You can read about more stories from Massachusetts CDCs by checking out our Notebook archive and the special newsletter that we published in collaboration with LISC Boston featuring stories from the field.